A chat with HTML Flowers

By Andy Summons. First published in Paper Sea Quarterly Vol. 4, Iss. 1.

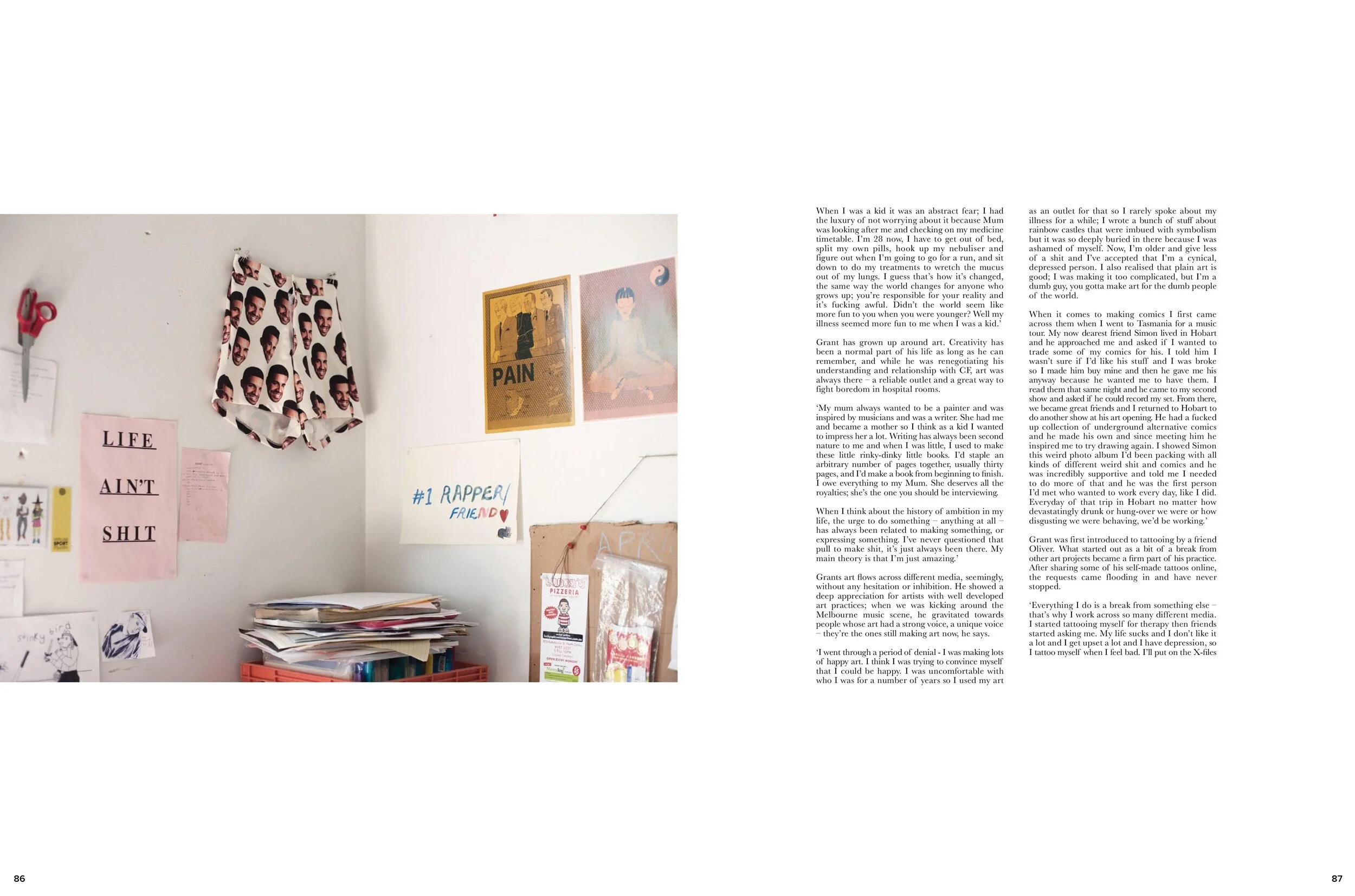

Grant Gronewald is an American-born twenty-eight year old artist now living in Melbourne’s inner northern suburb of Brunswick. He has Cystic Fibrosis (CF) but you’d be very poorly mistaken in thinking it defines who he is. His fiercely unique art effortlessly spans genres from drawing to hip hop to tattooing and, of course, comics.

Grant has a magnetic mix of nihilism, ferocious self-confidence, an immediate charm, and steadfast modesty, at least during our chat. It’s as if his trans-genre art practice is no big deal, just something anyone could do. Grant’s work is inspired by his mum and fuelled by a deep, lifelong need to create. His work often deals with deeply personal issues including CF, depression and his relationships, but still manages to maintain an upbeat and whimsical vibe. In short, his work makes us happy despite its darkness – a fair reflection of the man himself.

‘Life is such a fucking wasteland. It’s so important to make it meaningful for yourself otherwise you won’t survive. My first foray into art was through music, but the whole time I was recording and releasing albums I was hand stitching the covers and doing a drawing on each one. I was putting a lot of stuff online, doing shows and travelling a lot. I’d get fifty to a hundred people to gigs, which was a great success for what I wanted - I still can’t play an instrument. I’m just obsessed with words and sounds. So I’d play a terribly out of tune guitar and tell these disgustingly intimate stories about illness and hospital shit. At the time, my life expectancy was eighteen years old, so I thought I was going to die soon.’

Grant has Cystic Fibrosis – a recessive genetic illness that usually affects the lungs and pancreas, which results in an excess of thick mucous. For Grant, that means an on-going chest infection, thirty pills a day, about three two-week hospital stays a year, and working against a new level of consuming tiredness that gets worse every day.

‘Comparing my illness from when I was younger to now, I’m just so much more tired, you know? I feel like I understand it better. You know what it’s like when you fall in love and hang out with them for the first few times and it’s just gorgeous and then five years down the road there are so many things you hate about them but you feel like you need them so much – it’s like that with my illness. I wouldn’t be who I am without CF but at the same time I’m constantly tired. I wake up tired, I go to bed tired, I do everything tired and that only gets worse the older I get.

When I was a kid it was an abstract fear; I had the luxury of not worrying about it because Mum was looking after me and checking on my medicine timetable. I’m 28 now, I have to get out of bed, split my own pills, hook up my nebuliser and figure out when I’m going to go for a run, and sit down to do my treatments to wretch the mucus out of my lungs. I guess that’s how it’s changed, the same way the world changes for anyone who grows up; you’re responsible for your reality and it’s fucking awful. Didn’t the world seem like more fun to you when you were younger? Well my illness seemed more fun to me when I was a kid.’

Grant has grown up around art. Creativity has been a normal part of his life as long as he can remember, and while he was renegotiating his understanding and relationship with CF, art was always there – a reliable outlet and a great way to fight boredom in hospital rooms.

‘My mum always wanted to be a painter and was inspired by musicians and was a writer. She had me and became a mother so I think as a kid I wanted to impress her a lot. Writing has always been second nature to me and when I was little, I used to make these little rinky-dinky little books. I’d staple an arbitrary number of pages together, usually thirty pages, and I’d make a book from beginning to finish. I owe everything to my Mum. She deserves all the royalties; she’s the one you should be interviewing.

When I think about the history of ambition in my life, the urge to do something – anything at all – has always been related to making something, or expressing something. I’ve never questioned that pull to make shit, it’s just always been there. My main theory is that I’m just amazing.’

Grants art flows across different media, seemingly, without any hesitation or inhibition. He showed a deep appreciation for artists with well developed art practices; when we was kicking around the Melbourne music scene, he gravitated towards people whose art had a strong voice, a unique voice – they’re the ones still making art now, he says.

‘I went through a period of denial - I was making lots of happy art. I think I was trying to convince myself that I could be happy. I was uncomfortable with who I was for a number of years so I used my art as an outlet for that so I rarely spoke about my illness for a while; I wrote a bunch of stuff about rainbow castles that were imbued with symbolism but it was so deeply buried in there because I was ashamed of myself. Now, I’m older and give less of a shit and I’ve accepted that I’m a cynical, depressed person. I also realised that plain art is good; I was making it too complicated, but I’m a dumb guy, you gotta make art for the dumb people of the world.

When it comes to making comics I first came across them when I went to Tasmania for a music tour. My now dearest friend Simon lived in Hobart and he approached me and asked if I wanted to trade some of my comics for his. I told him I wasn’t sure if I’d like his stuff and I was broke so I made him buy mine and then he gave me his anyway because he wanted me to have them. I read them that same night and he came to my second show and asked if he could record my set. From there, we became great friends and I returned to Hobart to do another show at his art opening. He had a fucked up collection of underground alternative comics and he made his own and since meeting him he inspired me to try drawing again. I showed Simon this weird photo album I’d been packing with all kinds of different weird shit and comics and he was incredibly supportive and told me I needed to do more of that and he was the first person I’d met who wanted to work every day, like I did. Everyday of that trip in Hobart no matter how devastatingly drunk or hung-over we were or how disgusting we were behaving, we’d be working.’

Grant was first introduced to tattooing by a friend Oliver. What started out as a bit of a break from other art projects became a firm part of his practice. After sharing some of his self-made tattoos online, the requests came flooding in and have never stopped.

‘Everything I do is a break from something else – that’s why I work across so many different media. I started tattooing myself for therapy then friends started asking me. My life sucks and I don’t like it a lot and I get upset a lot and I have depression, so I tattoo myself when I feel bad. I’ll put on the X-files

or some reality show about prisons and tattoo myself. Sometimes I really want to tattoo somebody, leave a mark on them and do a cool design that means something to me, and other times I fucking hate doing it but I really need some money.

I see tattooing as witchcraft in the most grounded sense, in the same way that horticulture was once considered a form of witchcraft. Putting your energy towards a practice or an object or a ritual is essentially what witchcraft is about. Tattooing is a beautiful form of witchcraft in the sense that it allows you to honour something you care about. Sometimes I get commissions that are beautiful and so severely intimate to the person I’m not totally sure why they’d come to a stranger to do it and that is a beautiful process.

I love figuring out how to make something iconic; if someone asks me to do a sunset, I can’t do a photo realistic sunset and I wouldn’t want to, but figuring out the simplest ways to illustrate the sun and clouds is one of my favourite things to do and that translates across almost everything else I do. I enjoy that because everyone wants life to be simple, right? It just feels good to make something simple; you understand it and you’re in control of it and it can sorta feel like it understands you.’

An almost spiteful honesty permeates Grant’s art. He speaks freely about his depression, his relationship with CF, drug use and abuse, and his indifference to anyone’s opinion of him or his work. One thing became abundantly clear very quickly, Grant has figured out how to make two consuming illnesses work for him - CF and depression have become Grant’s biggest motivators.

‘Approaching my first life expectancy was when I first began dealing drugs. I’d force-quitted an old project and started a new one, which entailed taking a bunch of acid and recording heaps. I split up

with my partner of the time and told her I had to get out of life and that she’d be better off without me, so I went on tour. Before I left I bought a bunch of drugs and sold them to fund the tour while also taking a whole bunch too. It was supposed to be this huge drug paradise to end my life, but it didn’t happen like that at all.

I was supposed to be on tour for six months but I was out of money after three months. I’d upset the people I was staying with, can’t possibly imagine how, and I thought fuck it, I’m just gonna go home and die in my bed. I was just so unaware of how the process of dying from Cystic Fibrosis would start. Since childhood, I’ve always done everything I could to ignore the things doctors tell me because it all seemed so useless. I’m getting better at listening now, but I just thought I’d just keel over and die within a week.

Eventually I went to see my doctor, she did a bunch of tests on me and she said I was much healthier than she expected for a dead guy. Everything in my files suggested I should be much sicker, so we had a really honest holistic conversation about my lifestyle; like how much I exercised, my diet and things like that. So currently, my life expectancy is 35 years. A lot of people tell me not to put too much stock in it, especially with my depression, but I’ve lived with depression and life expectancies for so long that it’s actually valuable to me. It motivates me every day to get out of bed and do something meaningful with my time. There’s a very unique fear mixed with my run of the mill clinical depression that keeps me motivated to express the depression because I am so afraid of dying, and I’m also too depressed to have self-doubt because nothing means anything. I have nihilistic tendencies, but I like to think I’m not a dick about it. I’m nice to people I just don’t care about things.’

A lesson in perseverance and packing more cameras.